“Wait, Do You Have Children?”: The Domestic Horror of “Ghosts in the Burbs”

(This article was originally published on the Simplecast Blog on October 24, 2023)

Liz Sower is a suburban mom living in an upscale community just west of Boston. She has latent psychic powers and has gradually become more and more involved in the battle against the paranormal that seeps out of every window and door in Wellesley. Once just a spectator, she’s now on the radar of various entities with their own agendas. She’s also a mother, wife, and former children’s librarian who has to get her kids to sports practice and socialize with the neighbors, both haunted and not.

In our world, Sower is also the creator of Ghosts in the Burbs, a fiction podcast that has been running since 2016. Inspired by a lifetime of scary stories, Sower started the show under the guise of a blog and podcast devoted to collecting stories of the hauntings in her town. In the years since, Ghosts in the Burbs has become a cult favorite among podcast listeners, some of whom have been dismayed to find out that the stories are, in fact, fiction. But Ghosts in the Burbs, with its equal helpings of shadow people and PTA meetings, is domestic horror for our modern age.

Domestic horror is, as author Nathan Balungrud put it, based on the family. It takes what’s familiar and puts a monstrous twist on it, dropping you into a situation in which you would otherwise think you should be safe. Parents caring for their children, the security of a comfortable home: these are things you take for granted. The frightening imagery in these situations has a two-fold impact, providing multiple ways for you to approach the story you’re hearing. The monster might represent something that families have to deal with in the real world. Topics like addiction, death, and trauma are often symbolized by supernatural phenomena. But then, the surface story is just as horrific. Not only are these innocent children impacted by the fears of the adult world around them, they’re also being chased by a demon with no way to protect themselves.

Many popular horror movies fall under the umbrella of domestic horror; 2018’s Hereditary is one of the most famous in recent history. A grieving family is torn apart, literally and figuratively, by a demonic presence that’s been a part of their life for generations. 2019’s Us takes a similar approach, with evil doppelgängers threatening to murder and replace the families in the film. In 1982’s Poltergeist, two parents deal with a malicious presence in their new home that tries to prey on their children. The fear and desperation of the parents in all of these scenarios as they try to keep their children safe infuses the horror in a way that makes it far more personal than many other types of scary movies.

Horror author Isha Singh takes this idea a step further, stating that pop culture has “glamourized domestic life as the suburban ideal.” When that ideal is shaken, often by women stepping away from their assumed role in this space, the results are horrific. Domestic horror makes this idea the center of its appeal: women fight for a life outside of obedient homemaking and suddenly, the safe world they knew is no longer secure. Monsters wear the faces of their loved ones, and those who have stepped away from their roles are pressured to return to them by any means necessary. Singh uses the examples of The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins and Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby to demonstrate the ways in which ordinary women become entangled in domestic horrors when they dare to stray from their roles. Likewise, Helen Oyeyemi’s White is For Witching and Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle present the house in question as a character of its own; an agent of evil, or possibly twisted protection. The characters in all of these books can try to have their domestic lives as well as their freedoms, but they usually cannot save both. This is the fate facing Liz Sower’s alter ego in Ghosts in the Burbs.

What Sower manages to do within Ghosts in the Burbs is to show us a woman trying her best to keep her domestic duties fulfilled in the face of utter darkness. The horrors awaiting her in the forest beyond her neatly landscaped yard can’t come before the safety of her children, yet they still need to be addressed. And as the series progresses, those horrors come much closer to home, making Liz less of an observer and more a part of them. Just as the women in Levin and Perkins’s novels stepped out of their roles and into the darkness, Liz’s expanded consciousness leaves her unable to escape what’s coming.

Each episode of the podcast has a similar framework: Liz is contacted by a Wellesley townsperson with a story to tell, usually wealthy suburbanites, with all the entitlement and bad behavior that this label implies. Early in the series, these stories are self-contained and Liz is the only connecting thread between them, beyond the setting and the genre. Gradually, the series opens into a wider world of paranormal phenomena in this town and in certain locations beyond it. However, even as the series expands, it never loses its firm roots in domestic horror.

The first episode, “For Sale: Gorgeous Five Bedroom on Wooded Estate with Au Pair Suite (and Evil Housemate)” sets the tone for the series. Liz meets Becca, a beautiful fellow mother, at the playground in order to get her first story for the blog. As the mothers push their children on the swings, Becca shares her story about a malevolent entity in her home. It torments her, yet her husband refuses to believe it’s there. She tells a story of postpartum depression, the isolation of raising children, and the expectations and gender roles within marriage. Becca alone is responsible for not only keeping her home tidy and her child fed, but also for keeping them safe from the monster in the cellar. Becca’s husband is unwilling to believe her when she says there is something in their home and that they are in danger. Likewise, he refuses to help with the domestic chores as Becca drowns in child-rearing. It isn’t until he himself is impacted by the monster that the family can finally act.

Using only her narration, Sower unfolds Becca’s story. The horror in the telling is interrupted by mentions of pushing a baby on a swing, or of taking out cereal for the children to eat. At one point, Becca mentions something about “tummy time” – an important part of infant development where babies strengthen their neck muscles – and Liz interrupts her to ask about the pillow she uses for her child. These little details emphasize the mundanity of the suburban playground setting. In another story, they might be the focus of the narrative. But here, they contrast with the monstrous presence Becca has in her home. Sower’s depiction of Becca in the narration is riveting, pulling you helplessly toward a destination you’re dreading. Then, the episode ends on a gut punch of a line, something that reminds you that you’re in the hands of a horror master, even if she is dressed in Lululemon and feeding Cheerios to her children.

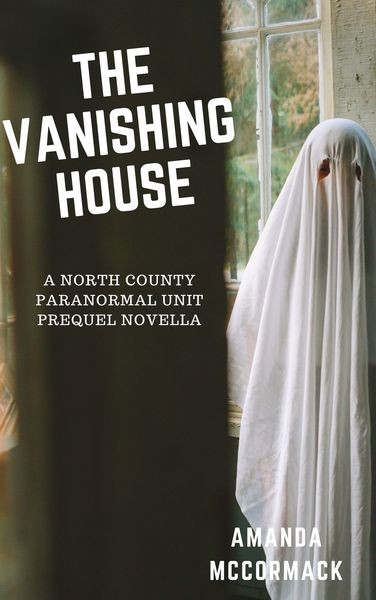

From this shocking first episode onward, profound horror intertwines with unremarkable reality in ways that provoke laughter and genuine fear. The domestic isn’t something to be mocked in Ghosts in the Burbs. Liz is not above her surroundings, domestic life isn’t a burden, and she acknowledges herself to be just as much of a typical wealthy suburbanite as her peers. Throughout the series, she drinks too much (something Sower addresses with sensitivity in a connected novella), judges the people around her, and makes mistake after thoughtless mistake. But she also grows, both as a person and with regards to the powers that make themselves known later in the series. She links up with a group of friends and collaborators as the stories connect into a giant web with Wellesley at the center.

In Liz’s world, horror and domesticity share the stage. She has that life which Singh talked about, the suburban ideal, but it isn’t the paradise we all hope it will be. Instead, it remains a complicated place, filled with monsters. In one episode, fairies have infiltrated the home of Liz’s yoga instructor. While the instructor and his wife see themselves as good people who just want to spread light in the world, they can’t resist the possibilities that the fairies offer, even as they hurt other people. In another episode, an old friend might be a danger to his family, whether he wants to be or not. Beneath each paranormal nightmare, a family suffers. While many stories use families and home solely as bloody fodder for the monster, Sower uses that familiar, sympathetic space to sharpen the edge of her dread.

One memorable episode has Liz meeting with a woman, Frankie, at the public library. Frankie swears she’s in contact with aliens and tells Liz a long, horrifying story about how these aliens are experimenting on humans and will come back soon to end the human race. She says the aliens have threatened to kill her whole family if she tells anyone and she doesn’t want to burden her husband with this knowledge. When Liz demands to know why Frankie told her, Frankie says she had to tell someone and that it’ll be over soon, anyway. Then, as though it never occurred to her before, she asks if Liz has children. The episode ends with Liz trying to detach herself from the story Frankie told. She keeps her daughters close to her all night, trying to convince herself that her reality is home and children, not aliens and monsters, no matter what the evidence tells her otherwise.

Ghosts in the Burbs’s success can be attributed to this combination of domesticity and earth-shattering horror. Beneath this world of school projects, marital friction, and mean girls lies another, this one filled with an evil that threatens the mundane world above, where our children innocently play. But just because the demons need to be battled does not mean you can miss preschool pickup. For many listeners, especially those with domestic duties of their own in a scary and unpredictable world, Sower’s stories make them feel seen.